... and the true legend of how Yuval Mishli replaced a radiator in a rented jeep in the middle of the desert

*I wrote this article in 1982, based on a letter I had written to family shortly after our desert adventure in 1978*

* * *

The Sinai captivated me the instant I crossed its border south of Eilat. The serene turquoise of the Red Sea to the east contrasted with the jagged granite mountains to the west. Solitary palm trees attested to life-giving water deep beneath the parched and rocky surface. The Sinai has always been a land of contradictions.

This was my first trip to the Sinai, in April 1978, only a few months after Egyptian President Anwar Sadat had come to Israel and offered us peace. We Israelis welcomed peace. But we sensed a treaty would stipulate the eventual return of the Sinai to Egyptian rule, and possibly restrict our travels there. Sixty thousand Israelis headed for Sinai that week to spend the Passover vacation. Most sought only the sun and beaches of the Red Sea, and did not head inland, as did my seven friends and I, to explore the wilderness. Yet, I believe, we all shared a sense of urgency, a longing to reach Sinai before the opportunity might be denied us. It was, perhaps, the exodus in reverse.

Prelude — the road to Eilat

The eight of us packed ourselves and our gear into two subcompact cars and left Jerusalem hours before dawn on Sunday. We wanted to reach Eilat before the tourists. We hoped to find a jeep for rent, as we had been unable to secure one by phone before the trip.

I shared my car with Yuval, Rayah and Yossi. Yuval, an engineering student, was the captain of this expedition: he performed the invaluable functions of driver, navigator, and mechanic. His cousin, Rayah, a special education teacher who craved a vacation, was the only professional in this collection of students. Her friend, Yossi, who preferred to be called Joe, was jolly, spirited, and a fine lastminute addition to our group.

Stocky red-haired Menahem, known as Gingi, drove the second car and served as co-captain. He and Yuval were our Sinai experts. They had spent their three years of service in the Israel Defense Force here. Stationed near the Suez Canal, they had survived the Egyptian attack and witnessed the deaths of friends during the 1973 Yor Kippur War. In his car, Gingi took his girlfriend Effi, and a fellow law-student named Dani and his girlfriend Leah. Leah and Effi were classmates at Bezalel Art School, where Joe also studied.

A two-lane highway and five hour drive links Jerusalem and Eilat. We passed through the semi-arid Dead Sea valley and Arava prairie which themselves beckon exploration. At the time Sinai beckoned stronger.

I found Eilat busting out like an adolescent. Homes, roads, entire neighborhoods had sprung up since my last visit several years before. I wondered how much more the town could expand, for there are mountains to the west, the Arava prairie to the north, and the Jordanian border to the east. If the Sinai were relinquished, the Israeli-Egyptian border would lie only a few kilometers south of Eilat. Eilat’s vitality stems from its southern quarter: the shipping port and the beaches in the Gulf of Aqaba. Curtailing Eilat’s growth in that direction could stunt the growth of the entire town.

A jeep for the journey!

As throughout Israel, Sunday is the first day of the workweek. That Sunday was also the first day of a vacation week. I could not distinguish the natives from the tourists in Eilat, since everyone was clad in swimsuits and shorts.

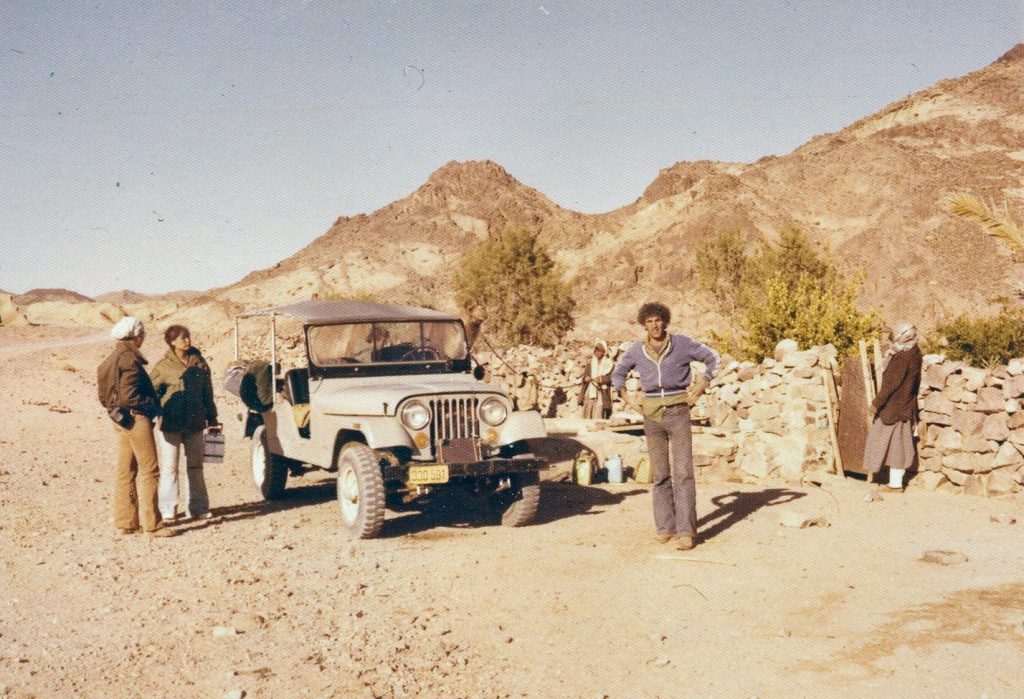

After visiting several rental agencies, we found a canvas-top jeep. The eternal optimist, Yuval declared, “I told you so.” Gingi laughed with delight. Dani was incredulous. I, too, was amazed by our good fortune. With paperwork completed, we readied the jeep for its four day journey. We tied our knapsacks to the rollbars around the jeep, and crammed the well (meant for our feet) with crates of food and jerrycans of water. Dani, growing concerned with the piles of equipment, asked, “Do we need to pack the tool kit?

Yuval, an optimist, but no fool, replied, “Of course. We’ll make room for it.” Covering the gear with layers of unrolled sleeping bags allowed five of us to lounge in the back with our outstretched legs dovetailed. Two more squeezed into the front seat with the driver. This cozy arrangement was not comfortable, but it promoted camaraderie.

Nuweiba

Our first destination was the beach at Nuweiba, an hour south of Eilat.

There we stopped for a swim in the Red Sea and a picnic lunch under one of the many palm trees which shade the shore. Bedouin fisherman have dwelt at this oasis for centuries; Israelis for only a decade. But already the Israelis had established a thriving farming community and a two-star resort. Neviot (“bubbling springs”) — as it is called in Hebrew — was the tangible product of ideology and ambition. I could not conceive of abandoning it.

As I sat on the fine white sand I stared at the ochre mountains of Saudi Arabia beyond the azure sea. I had never seen that country before. As an Israeli citizen I would never be permitted to cross its borders. It was not the sea that confined me, but the chains of political animosity. Perhaps this is why I had come to Sinai. I wanted to combat the claustrophobia that comes from living in a country surrounded by five hostile neighbors — Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Saudia and Egypt. Perhaps that is why I am so eager for peace with Egypt, yet regret the Israeli evacuation of Sinai.

After a lunch of jam on matzah and canned fruit, we climbed back into the jeep. Gingi took the wheel from Yuval. He tested our jeep by giving us a rollercoaster ride up and over sand dunes as we scooted away from the crowds whose cars and tents would make this beach a strange shanty village.

Wadi Saal

We continued south on the main highway, then turned off onto the unpaved road in Wadi Saal. This track leads to Santa Katarina, the outpost near Saint Catherine’s Monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai 100 kilometers away.

Wadi Saal is typical of the river beds which traverse the Sinai. It is bounded by precipitous granite walls which often come within meters of converging. With little vegetation to absorb the winter rains, the wadi becomes a channel for flash floods. In spring, however, only watermarks, puddles and slight trickles remain.

The jeep performed admirably, and we barreled along this gravel road as if it were asphalt. Dust swirled up from the rear tires and coated our skin. It did not, however, cloud the view, which seemed to be a lunar landscape except for occasional spindly trees emerging from crevices in the crags.

Halfway to Santa Katarina, the wadi now an open expanse, we came across a single thatched hut displaying a sign “coffee shop”. No traveler can ignore an oasis: we stopped for a cup of coffee. And, as a Bedouin tends first to his camel’s needs, our pit crew, the four men, scanned the jeep to see how it had fared on the first leg of our journey. They found a leak in the gas tank.

We set to work preparing the Israeli army’s remedy for leaking tanks -chewing gum. The Bedouin innkeepers approached curiously, then offered us their method — a bar of soap. A bus driver (he happened to be an acquaintance of Yuval), who had just stopped here on his way to Santa with a touring group of youngsters, offered us the best solution — epoxy glue.

Once the leak was plugged, we sat and drank demitasses of gritty black coffee served by the Bedouins. These men resembled Bedouins I had encountered elsewhere. They wore dark tailored jackets over their robes. Their heads were covered by white keffiyehs, their feet in sandals. Their leathery skin suggested they did not need the protection of such clothing from the heat of the day or the chill of the nights in the Sinai. I noted one difference in these Bedouins. They were selling hospitality — a commodity most Bedouins dispense freely.

Breakdown!

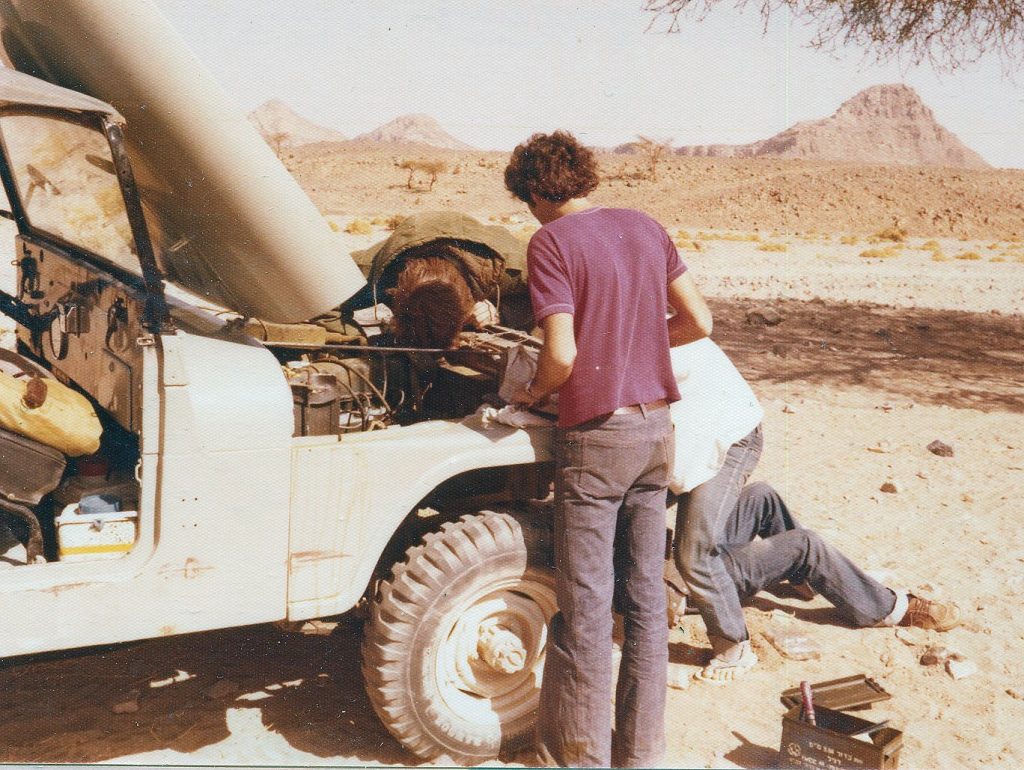

We had only gone another two kilometers toward Santa Katarina when Dani, who had just taken over the driving, cried out, “I’m getting sprayed with water!” “Stop the jeep!” Yuval commanded.

The reason for the sudden shower stunned us. A stone had bounced up, gotten caught, and bent one of the propellers of the fan which, as it spun, sliced through the radiator hoses. Without a radiator to cool the engine, the jeep could go nowhere.’ It was already late afternoon and logic told us to return to the Bedouins! encampment to spend the night. It was a landmark, had a water tap, and maybe we could again find help there. Yuval maneuvered the jeep back to the coffee hut.

Yuval’s bus driver friend was still there. This time, however, neither he nor the Bedouins could help us. Automotive trouble is always inconvenient. But the nearest garage, or even any means of transportation or communication, was hours away. We were stranded. Only the company of friends prevented my apprehension from turning to panic.

Our attention was drawn to a broken-down Studebaker pick-up truck sitting on wheel-rims next to the Bedouins’ hut. The truck was being used as a playhouse by the Bedouin children. Yuval raised the hood; the engine was there, but the radiator was not. The sun, now sinking rapidly behind the wadi walls, reflected our mood.

Scavenging a new radiator

Suddenly, Dani, who was collecting sticks for firewood, let out a cry of delight: he had found the radiator of the truck on the ground. It was dilapidated, but comparable to our jeep’s radiator, and just might work. The Bedouins, keen to our plight, demanded a price twice that of a new one. We refused. We argued politely, but they stubbornly clung to their price. Tourism had turned these Bedouins into businessmen.

An army patrol arrived after dark. When we told the soldiers about the radiator, one of them spoke to the Bedouins in Arabic and persuaded them to lend us the radiator. We promised to return it as soon as we had replaced or repaired our damaged one. The Studebaker’s radiator was now ours. But would it work?

For the moment we were relieved, and that question would remain to be answered. We were hungry, and feasted on the steaks which had been defrosting in the cooler since our leaving Jerusalem that morning. Relaxing by the glow of the campfire, I reflected on the simple splendors of Sinai which I had come to know that day: the penetrating sun, the refreshing sea, and now the brilliant full moon and the stars which blanketed the sky. I had never before felt so close to the heavens, as if I could reach out and grasp one of the stars. In this vast wilderness I felt meek, yet enthralled.

I was also very tired. By nine o’clock we were all asleep except for Yuval and Joe who worked by flashlight on the radiator until midnight.

Up and onward

The sound of Yuval laboring at the jeep woke us Monday morning. Over breakfast he explained the radiator did not exactly fit our jeep. He and Joe had pilfered assorted parts and pieces from the Studebaker and a nearby steel-wire fence. Yuval had used them to extend and connect the main hoses of the radiator to the corresponding inlets and outlets and, since the bolts did not match the holes, to tie the radiator to the jeep. For his ingenuity, Yuval deserved his engineering degree a year early.

The air was cool and breezy, and we kept on jackets, even as the morning lengthened. We found we could stay warm by sitting close to the ground. Thus the wind blew over us while the sun’s rays penetrated. The day remained chilly.

We were packed and ready to take off by eight o’clock. But the jeep was not ready: the makeshift radiator interfered with the steering shaft. The entire pit crew went to work this time, while we women, in true Bedouin fashion, tended to the flock of scrawny black goats which had wandered our way looking for breakfast scraps. I had not seen these animals the night before and wondered where they had come from. As the trip progressed, I concluded, as have many other Sinai travelers, that Bedouins and their animals simply materialize.

Grateful to be on wheels once again, yet fearful of damaging the radiator, we committed ourselves to a slow pace, punctuated by water-filling stops. We were in no rush. Our mishap with the jeep had precluded our plans to hike up Mount Sinai at dawn. A climb at that hour avoids the usual heat and affords a view of sunrise over the Gulf of Suez to the west and the Gulf of Aqaba to the east — a panorama the width of the Sinai peninsula. Our view of the land from the gully between the granite mountains was not as spectacular as the one from the peaks, but was still awesome.

Santa Katarina

Nearing Santa Katarina, a sudden blessing surprised us: our jeep alighted on a paved road. This stretch of five smooth kilometers is an example of the Israeli government’s efforts to make the landmarks of Sinai accessible to tourists. With the possible withdrawal from the Sinai, however, it was unlikely Israel would finish paving this road.

We reached the settlement of Santa Katarina by late morning. We brought the jeep to the local garage– a thatched hut with standard spare parts and basic repair equipment. The Bedouin mechanics could patch the gas tank, but could do nothing for our shredded radiator.

While we waited, we toured this settlement — a collection of stone buildings comprising a post office, a general store, a gas station, a government office and a restaurant — a Middle Eastern Dodge City. The amenities in this remote area impressed me.

We treated ourselves to lunch at the restaurant. Seated at a picnic table on the porch, we ate a filling lunch of pita bread dipped in humus (mashed chickpeas) and heavily sweetened tea.

Afterwards we collected the jeep and drove to the path leading to the fortressed Saint Catherine’s Monastery. This bastion was built in the sixth century at the site believed to be where God spoke to Moses from the Burning Bush. It nestles beneath the mountain on whose peak Moses received the Ten Commandments. Mount Sinai is also known by its Arabic name, Jebel Musa – the Mount of Moses, whom Moslems revere as a prophet.

A few members of our group made the fifteen minute hike to the gate, but could not get inside. Only scheduled visitors are privileged to tour the monastery and see the art and artifacts which a handful of Greek Orthodox monks have committed their lives to protecting. The monks, understandably, prefer their solitude to the clamor of inquisitive tourists.

My disappointment at not climbing Mount Sinai or seeing more of Santa Katarina was countered by my conviction that I would visit the Sinai again, no matter who controlled it. What I had seen so far had intensified my historical, religious and emotional ties to Sinai. This trip alone would not satisfy my appetite to know and understand this wilderness and its inhabitants.

Feiran (Pharan)

Our next destination was Neveh Feiran, the largest oasis in the southern Sinai. Although Neveh Feiran is only about 60 kilometers from Santa Katarina via Wadi el Sheikh, it took all afternoon to reach. The road was again rocky and we jounced in unison. Inexcusably harsh jolts of the jeep prompted a warning chorus of “Radiator!” to the driver.

The settlement at Neveh Feiran resembled the one at Santa Katarina -simple buildings of cemented brown stones. An archeology team had exclusive rights to the hot water bathing facilities. Some distant boulders, a cold water faucet and the jeep’s rear view mirror served our needs.

At dinner that night we invited a curious Bedouin to make us pita bread. In anticipation of such an opportunity, we had packed a bag of flour and a metal cafeteria tray to place on the coals. The recipe was simple: flour, a pinch of salt, and enough water to make a dough. Rolled and flattened like a pancake, the dough was set on the hot tray. As soon as bubbles appeared, the dough was flipped over. This quick baking creates the bread’s pocket. We thanked this Bedouin with a can of olives and some Passover matzah. The matzah especially pleased him. He explained it was not nearly as harsh on the digestive tract as the pita.

Although we were camping in the middle of the wilderness, we were also on the fringe of a settlement. We knew that “settled” Bedouins differ from their brethren in more remote areas of the Sinai. To safeguard our belongings that night, we slept next to the jeep in a circle around our equipment.

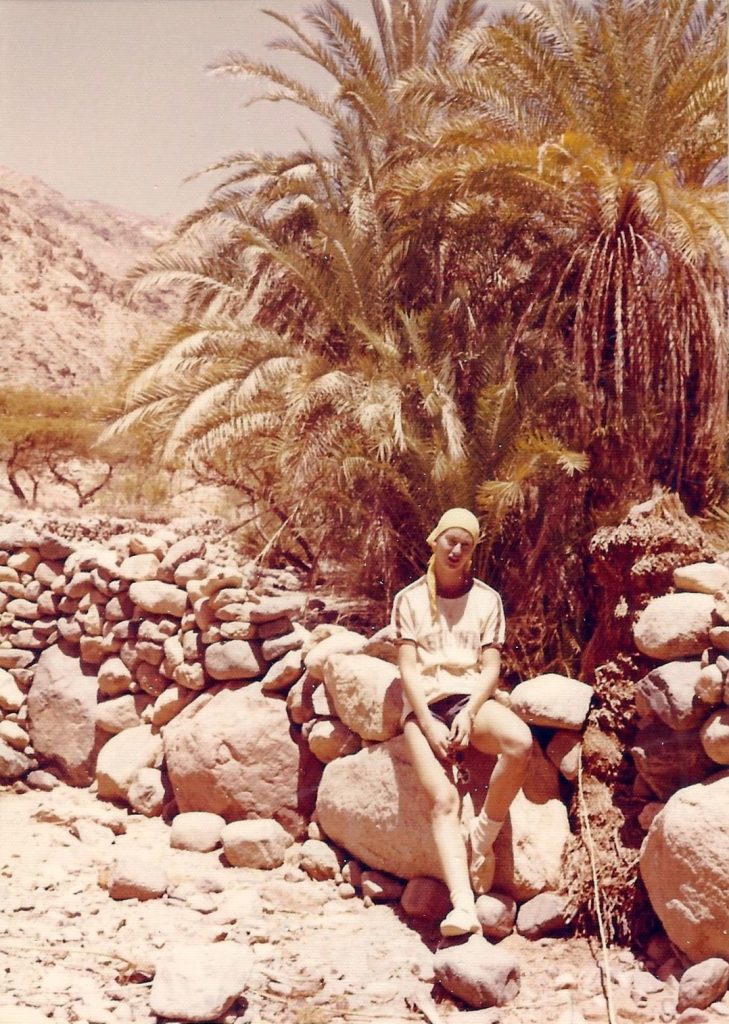

The morning was already warm when we awoke on Tuesday. It was a fitting day to drive through the stretch of Wadi Feiran which was lush with palm trees and bustanim, walled-in gardens cultivated wherever the Bedouins find enough water to fill a well, and thus support life of all forms. Surprisingly, there are many such gardens throughout the Sinai. Some wells are fed by rubber hoses which transport the water from fuller wells. These hoses lie exposed on the wadi floor, yet nobody ever damages or removes them.

Near the end of the Feiran oasis, we saw a huge bundle hanging from a tree. We understood it contained the belongings of a Bedouin family which had left its home temporarily. Bedouin traditions protect these possessions. We backtracked to the settlement, thus enjoying a double dose of greenery. The term “Sinai desert” accurately describes northern Sinai. It does not apply to the southern part of the peninsula.

Wells may be plentiful in this wilderness, but gas stations are not. We stopped at Naveh Feiran for gas, even though Yuval figured (the jeep’s gas gauge did not work) we needed only a quarter of a tank. When an entire tank of gas went into the jeep, we realized some sly Bedouin had siphoned our gasoline during the night. The gas had not leaked. Bedouin customs of respecting unprotected property apparently did not apply to us strangers.

Nawamis — prehistoric tombs

We followed Wadi Feiran past its junction with Wadi el Sheikh, until we reached a collection of round stone structures about three meters in diameter called nawamis. These doorless, windowless structures have stood for centuries. Scholars believe they were used as burial sites. I peeked through the cracks between the stones and saw skeletons.

At the nawamis we met a band of Bedouins in jeeps. We noticed they also used steel wires and tape to replace and repair broken parts on their vehicles. Our radiator interested but did not surprise them. These men directed us to the point, identifying it by rocks and vegetation, from which we could reach Wadi Hebran, our route to the coast. Sure enough, stone cairns, which are erected by Bedouins to identify trackless routes through the wilderness, helped us find the way.

Wadi Hebran

I soon understood why we had been advised several times to take this route.

The progressive layers of mountain ranges shifted from brown to grey to violet. The track narrowed as we descended into Wadi Hebran. The wadi floor was covered with stones which had been swept down from the mountains in the currents from winter rains. Meandering streams often crossed our path. They were not remnants of winter floods, but sprung from pockets of water which form in Sinai’s porous limestone. Such conditions probably caused the gush of water when Moses struck the stone. Wherever the streams grew to form small pools, tufts of grass and curlicue ferns sprouted.

We stopped to refresh ourselves at such a spot, where a cluster of palm trees invited us. Two Bedouins on camels suddenly appeared, from the same direction whence we had. Surely we had passed them earlier. But we had not. They had emerged — materialized — from the mountains. Their ornamented saddles and colorful woven blankets made us speculate later whether they were smugglers. We spoke a few words, nonverbally, took their photographs, and offered them cigarettes, which we smoked together. Then, as swiftly as they had appeared, they disappeared.

Eventually, the stream dried up, and the wadi opened into an arid plateau.

Moses’ bath houses

The landscape teased us visually until, two hours later, we reached the coast and the paved highway. Feeling triumphant, we sang praises to the radiator which had remained solid and allowed us to make this fantastic trek.

We could see the Gulf of Suez glimmering in the distance, with the coast of Egypt a blur beyond it. Heat waves shimmered in front of us while the dust clouded behind us. Vegetation was scant and no larger than spiny pale green bushes. An enormous lizard scooted across our path, as if to convince us that life could exist here.

Yuval’s navigation had been exact. After driving just a few kilometers south on this road we reached Hamam Sidna Musa, the Hot Baths of Moses. These hot springs have been harnessed into pools. Some pools are sheltered by palm trees, others are enclosed in adobe structures. The bath house we entered was dark and dank, but we plunged into the pool. Three days of Sinai dust wanted removing.

I sat in the front seat with Yuval as he drove towards Sharm el Sheikh at the tip of the peninsula. The warm bath and smooth highway soon lulled everyone to sleep. But I could not close my eyes. The late afternoon sun turned the distant mountains a hazy mauve, the sands a rich gold, and the sea a glittering cobalt. The tranquility of the scene was often interrupted by the rusted remains of armored vehicles, scars of the most recent episodes in the Sinai’s war-torn history.

Sharm el Sheikh

Ophira — as the modern settlement at Sharm el Sheikh is called in Hebrew — was a budding city at the time. The town boasted two supermarkets. The civilian store was closed, as are most Israeli businesses on Tuesday afternoon. (It makes up for working Sundays, I suppose.) The army store, the Shekem, was open. Joe produced a military identification card which gained him entrance. He and Rayah emerged half an hour later with eggs, cheeses and matzah. The shelves had already been cleared by tourists like us, who had run short on food.

After three days of relative isolation, we were taken aback by the bustle of Ophira. We were thus delighted to find, only a short distance from the main beach, an unpopulated sandy cove. It was an ideal campsite. We lit candles that night, not for the illumination, but because there was no wind to snuff them out.

Wednesday morning we lazed on the beach and swam in the temperate, lucid water. The masses of coral reefs just off shore are home to multitudes of exotic, colorful fish. We took turns using Dani’s snorkeling mask and my raft. It was our version of a glass-bottomed boat.

Reluctantly we left Ophira at noon and headed back to Eilat, a drive of six hours. On the long drive back I remembered, with regret, why I had foregone earlier opportunities to tour the Sinai. I had pictured travelling distances through barren, dull landscape. I had not imagined the Sinai’s spellbinding beauty or the vitality of the settlements. This trip had dashed my preconceptions. I wondered then whether a peace treaty would obligate Israel to return all of Sinai to Egypt. I wondered whether this first trip to Sinai would be my last.

Farewell

And now, on the eve of Israel’s withdrawal from the Sinai, my emotions conflict.

I am saddened. My heart aches for the Israeli people who must leave their homes in Sinai. These settlers believed their presence would ensure stability in the region. Their efforts were supported by the Israeli government and populace. As their settlements grew, so did their attachment –and the nation’s attachment — to the Sinai. But once the conditions for peace were determined, Israel became riddled with internal disputes over the fate of the settlers and the settlements. Some branded the settlers as obstacles to peace while others heralded them as the final harbingers of peace.

The heartbreak lies in abandoning the dreams so many settlers realized in Sinai. It is particularly painful when years of labor have been spent trying to fulfill these goals. The settlers can be financially compensated for the forced abandonment of their homes and even their livelihoods. They cannot, however, be adequately compensated for relinquishing their ideals. That is why Israel’s complete withdrawal from Sinai is a steep price to pay for peace.

But if peace will ensure open borders between Israel and Egypt, then I am gladdened by it. I will be able to return to Sinai. I will climb Mount Sinai. I have yet to do so, and I am still compelled. The ragged mountain ranges, the winding wadis, the lush oases and the enigmatic Bedouins will still be there to inspire. If, at most, I will need only a tourist visa to journey once again to Sinai, then, for me, Israel’s loss of Sinai will not seem so acute.