Succot – October 1995. Egyptian Sinai, the Gulf of Aqaba coast.

Three days with three families (6 adults and 9 children) from Maccabim

There ought to be a warning sign on the Israeli side of the Taba border crossing into Egypt: “Last Sanitary Pit Stop”. Although the bathrooms in the Lagona Village “resort” in Dahab were clean, the toilets barely flushed, and, since the water in the pipes is “salty”, large buckets of “sweet” water in each bathroom are provided for rinsing off after a shower. The first night of our stay we reported to the hotel clerk that we had no hot water; we were told there would be hot water “soon.” When we realized the second night that there simply was no hot water tank for our bathroom, we were moved to a room on the other side of the courtyard, which did have a hot water tank. That tank produced a trickle of warm water, not enough to shampoo our hair, but at least we could stand under the shower head and bathe. Since the running water is not potable, we brushed our teeth using bottled water. Indeed, we carried bottled water wherever we went, and drank lots of Pepsi during our stay. Aside from the one in our hotel room, we would not see a toilet again until we returned to Israel.

Egypt along the Gulf of Aqaba is like Gaza without the congestion or hostility. Like a third-world nation, it lacks an infrastructure and has no public utilities or services. Garbage is strewn everywhere, few roads are paved, street lamps and sidewalks are nonexistent. New apartment blocks look deserted, but hanging laundry indicates life in them. Not one Hebrew word is visible; nothing indicates Israelis ever inhabited this place. Although some buildings are clearly distinguishable as Israeli constructions, and are recognizable by the trees and plants which were planted years ago and still surround them, most have fallen into disrepair and blend colorlessly into the sprawl of Dahab and Neweiba.

The sights and smells were hard on the senses, but worse was the assault on my ears. Wherever we went, music on scratchy cassettes blared from tinny speakers on tape-players. Black rap-music, with a heavy boom beat, seems to be the most popular sound along the Aqaba coast. Sitting at the restaurant in “downtown” Dahab one evening, I discerned at least four different sources sending waves to my brain.

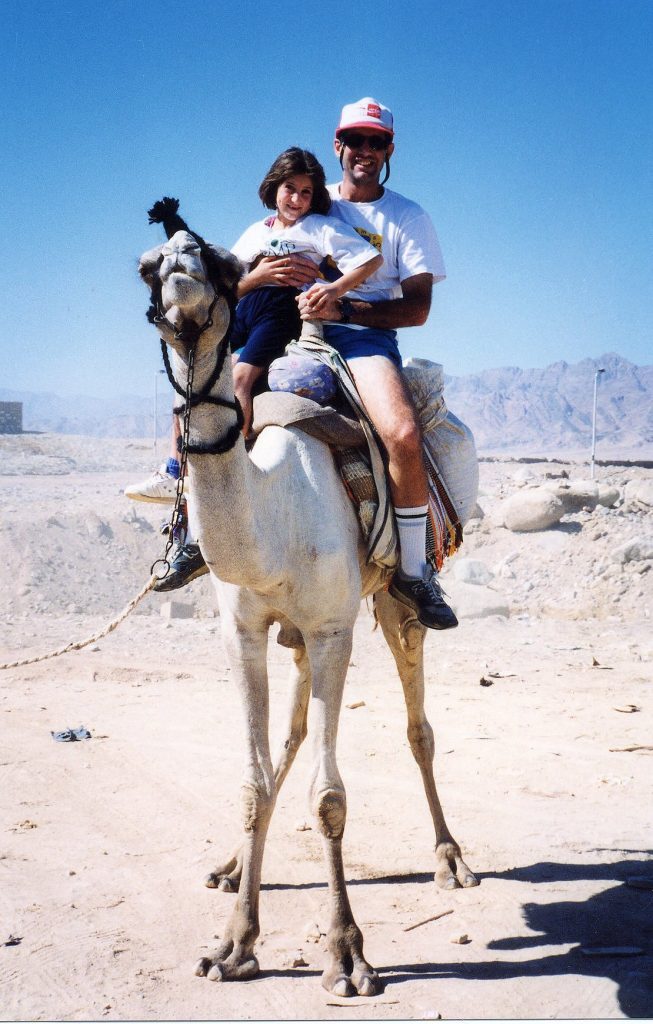

The Egyptians we got to know have all relocated from the main cities in Egypt to serve the tourist trade in Sinai. They all head home during seasonal lulls. Many speak decent English, and some a bit of Hebrew. They run the hotels, restaurants and shops. They are eager to serve and please, but have completely different conceptions of time and amenities. “Soon” means any time in the future, not necessarily within the hour; “toilet” means a hole in a shack out back. They treat our children wonderfully, indifferent to their rowdiness and bickering, fawning over them as a means of flattering us. Wherever we went, Amit drew attention. By the time we left Sinai I figured I could trade her for at least 300 camels.

The Beduoin are easily distinguished by their traditional dress–galabiyah robes and keffiyah head scarves. The Bedouin speak Hebrew, even though Israel relinquished control of the Sinai nearly a generation ago. A five year old Beduoin girl, peddling braided string bracelets, spoke to us in amazingly good Hebrew.

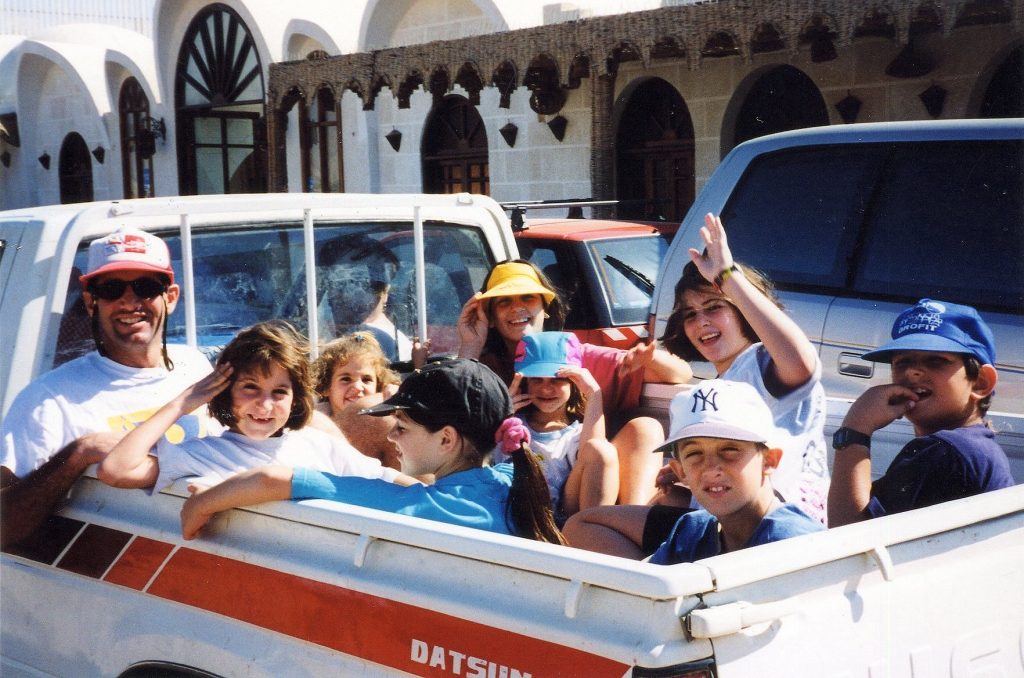

The Beduoin drive the “taxis”– pickup trucks with open cargo bays, into which 10 or more people can fit. They drive cautiously, though it is not clear whether they are concerned more for the welfare of their passengers or their vehicles. They often drive at night without lights, but always use their blinkers–even if there are no other vehicles anywhere in sight. But when another vehicle appears, they immediately beep their horns. The only time they drive fast is when there are pedestrians and other vehicles on the road.

We struck up a business relation with a Bedoui named Ch’med, who arrived promptly at any appointed hour to take us wherever we wanted to go. Ch’med told me he thought life was better when the Israelis held Sinai, although I didn’t understand his reason for saying so. I think it’s because the Israelis treated the Bedouin with greater respect and allowed them more freedom than the Egyptians do. Ch’med, for example, told us he could not enter our hotel lobby.

One night Ch’med took us to a secluded wadi near Dahab for dinner. The meal had actually been prepared in advance “in the village” (by the caterer, we joked) and he brought it in platters covered in tin foil. The chicken had also been cooked, and Ch’med simply finished baking it over hot coals. The kids did not particularly like sitting in the dark and stargazing, but Ch’med’s meal was the best one we ate during our stay.

We discovered the best food the locals know how to prepare is pizza, spaghetti and Greek salad (chopped vegetables with white cheese, no meat). Although fish, shrimp and calamari is on everyone’s menu, freshness is dubious. Some keep fish on display in the street outside the restaurant–which does more to suppress your appetite than to stimulate it. The trick is also to go into a restaurant before you get hungry. It takes a least an hour for all items ordered to reach the table. Amit fell asleep at the table long before her plate of rice and mushrooms arrived, and after we had been told at least five times that the rice would be ready “in two minutes”. Mohammed, our charming and personable waiter, did not charge us for the dish, and then offered it to two young women at another table, when he was unable to wake up Amit. Also, don’t think about hygiene, and never go anywhere near where you may catch a glimpse of the kitchen.You’re better off not knowing what it looks like.

Aside from Europeans, who come mainly to dive along the coral reefs, tourists on the Sinai coast are predominantly young Israelis in their late teens and early twenties. They park themselves in huts in front of the “cafes” and restaurants which line the shore. Apparently you can stay put as long as you want, as long as you occasionally order some food or drinks. Families with children, such as us, are not as common and appear to be more of the sporting and adventurous type. (I remarked feeling I was too old, and my children too young, to fit in at Neweiba.)

We spent the better part of one day snorkeling at the Blue Hole reef, north of Dahab. Since I can’t see without glasses, and didn’t risk wearing contacts under a mask, I simply watched as Yuval, Doron and Smadar and the others paddled around looking at fish and coral. Aside from two cafes and the snorkel rentals, there were no other facilities there. If you need “to go”, you either go for a swim, or you go for a walk up into the hills. I’m debating whether the lack of development is good or bad for these natural wonders. The lack of facilities probably keeps away the throngs of tourists who would wreck the corals; on the other hand, the lack of environmental protection is also detrimental. Looking at a map after our trip, I discovered that an area just north of the Blue Hole, like Ras Muhamed at the southern tip of Sina, is a designated nature preserve; I am curious to know if and how the areas are patrolled.

We had left our cars in Eilat and crossed into Egypt at Taba, where were met, by prior arrangement, by two 4×4 vehicles from our hotel. (We actually sat around for 45 minutes until we realized we were waiting in the wrong place.) One driver, named Bassem, spoke excellent English, and led us to believe he was the deputy manager of the hotel. (The hotel reception clerks later claimed he had no such status.) Bassem became our buddy, asking us if we would send him a book he could learn Hebrew from; we offered to send him a cassette, to listen to and practice with during his long drives. He gave us a passport photo of himself in army uniform. The other driver, named Ahmad, knew no English, and we were unable to communicate with him; but we did learn he had a wife, child and week-old baby in Port Said.

On our last day, we hired Bassem and Ahmad to take us back to Taba by way of an off-road trek. Yuval had brought his 20 year old maps of Sinai, and was not quite certain about where to turn off the (now paved) road to Santa Katarina into the wadi we wanted to travel. Fortunately, Beduoin peddlers as well as Egyptian solders are stationed along the road, and they all gave us proper directions. Neither Bassem or Ahmed had ever done 4×4 driving, and entered the sand-covered wadi with great trepidation. We thought they might let us do the driving, but they were not about to relinquish the wheel. Yuval tactfully instructed Bassem, who eventually got the hang of driving on sand (keep up your speed; slow down and you’ll get stuck) and began to trust Yuval’s ability to navigate. As his confidence grew, he relaxed, stopped smoking, and visibly enjoyed himself. When we reached Ein Fortaga, a Beduoin encampment along a spring-fed stream, remembered well from a visit years ago, we discovered it can now be reached by a paved road from Neweiba. So the off-roading ended sooner than expected as we hit the pavement and headed toward Neweiba and points north.

Bassem, who drives 15 hours between Dahab and his home in Alexandria, queried us as to why we wanted to trek through the Sinai, and found it difficult to comprehend our fascination with the landscape and beauty of Sinai. Truly the scenery is awesome, more vast and imposing than anything in the Negev. The mountains are massive and rippled with colors, gorges are deep and wadis are expansive, vegetation is rich, and especially lush near springs. The Bedouin with their camels and goats blend into these natural surroundings, adding color and life to the starkness. It is unlike anything we see on our jeep excursions in Israel.

As we drove back up the coast to Taba in late afternoon, the sea was mesmerizing with its varying shades of blue and turquoise. And scarcely a person on any of the beaches anywhere. When we had headed down the coast, we saw what we thought were abandoned hotel projects. We had pondered why the Egyptians were not making any efforts to turn this magnificent coast into a resort area. But coming back up the coast, we realized these buildings are simply being constructed at an excruciatingly slow pace. Like the hot water which will “soon” be available at the Lagona Hotel in Dahab, the Egyptians may one day be able to offer the accomodations and amenities expected by foreigners. Just don’t hold your breath. Though meanwhile, it may help to keep your nose and ears plugged.

Upon leaving Egypt, as we began passing through the shack which houses the Egyptian passport control, four busloads of African tourists entering Egypt also arrived, resulting in gridlock at the counter where passports are stamped. Our line was rerouted to another passageway, where we stood and stifled in increasing darkness for nearly an hour. At first we thought the Egyptians were conserving energy, but later realized the Egyptians were working by the light of emergency lamps. As soon as we crossed the barrier into Israel, we were met by bright lights, paved sidewalks, and a passport control terminal worthy of its name, complete with a water cooler, a kiosk and, best of all, immaculate restrooms.

Although my impression was that Sinai hasn’t really changed in the past 15 years, as compared to the massive tourist-related construction and development in Eilat, nearly everyone I have spoken to since my return is of the opposite opinion. They tell me Dahab and Neweiba were once small Bedouin villages next to which Israel established a small settlement and a beach front. They have now evolved into small cities whose residents cater to a thriving tourist trade. Others who remember Dahab and Neweiba better than I are impressed with the number of hotels, hostels, restaurants and souvenir shops that have opened up. None seems to be bothered by the slum-like atmosphere, and all tell me that I must go to Sharm-el-Sheik, which is really world-class.

I am in agreement with one of our traveling companions, who thought it inexcusable to be promised the imminent arrival of a plate of rice for nearly an hour, and incomprehensible to be promised a hot shower when a water boiler tank did not even exist. But our attitude was to find to the humor in it all, and we thoroughly enjoyed experiencing the Egyptian culture.